Historic Johnson County village is falling apart. Will Panasonic plant save or kill it?

Uniquely KC is a Star series exploring what makes Kansas City special. From our award-winning barbecue to rich Midwestern history, we’re exploring why KC is the “Paris of the Plains.”

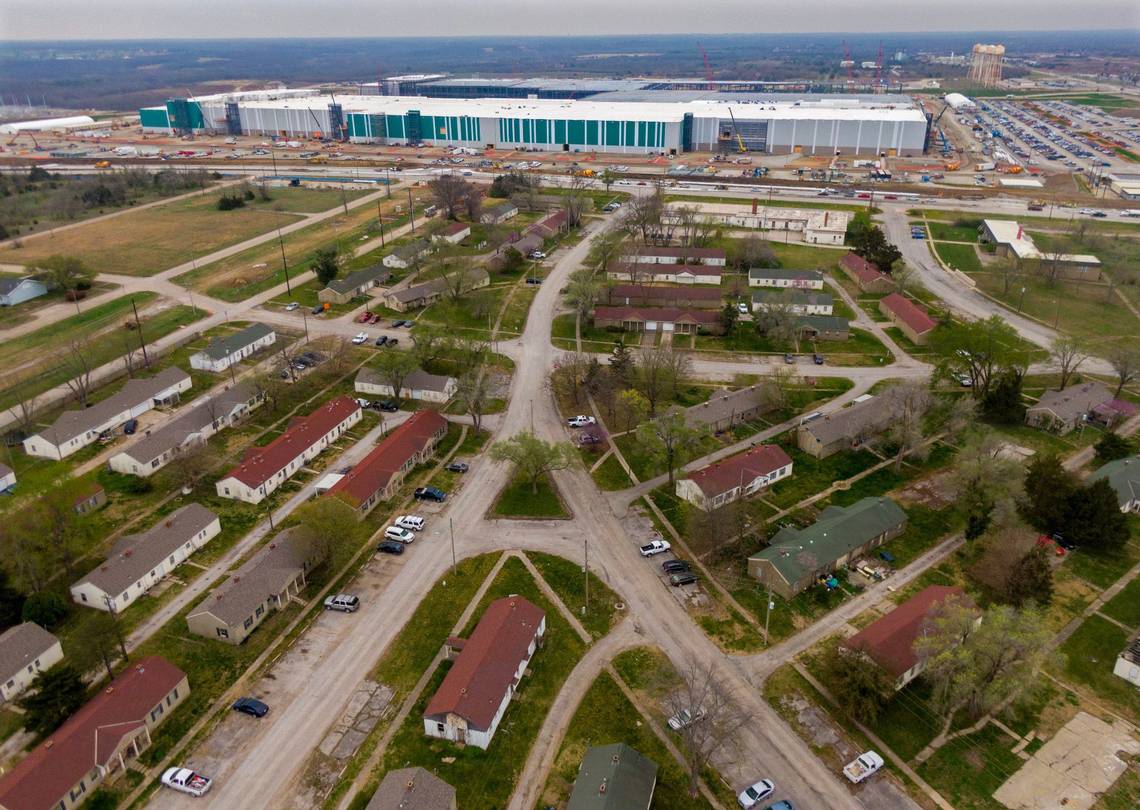

On the outskirts of De Soto, 70-year-old Wanda Riedhart wrenched open the wobbly aluminum door that scrapes the concrete pad at her home — a single-bedroom rental inside one of 164 concrete, barracks-like houses at Clearview Village.

Long in decline, the low-income neighborhood — a once thriving wartime community known for decades as Sunflower Village — was hurriedly built in 1943 to be “temporary housing” for some of the thousands of workers who flooded into rural Johnson County after Pearl Harbor. They came to work at the Sunflower Ordnance Works, built after the attack to become the era’s largest smokeless powder and propellant plant in the world.

Riedhart has in effect lived for 12 years in a place that was never built to last.

Eighty-one years on, it shows.

Dozens of the rectangular buildings now sit empty. Windows are broken or boarded with plywood. Paint is peeling. Wood is rotting. Weeds break through cracked sidewalks and asphalt.

Yet, in a manner as sunny as her hair — spiked and dyed a luminescent magenta — Riedhart insists she’s happy there. She especially loves the $760 per month rent. Two-bedroom, two-baths go for about $1,050. “Cheaper than anywhere else,” Riedhart said.

She likes her neighbors and loves that her job at Casey’s convenience store, where she starts at 2 a.m. to prepare doughnuts, is barely a mile off.

“I think I lucked out,” Riedhart said. “I have a great apartment. I have great friends that live right close. There’s nothing around.”

Except now there very much is.

Trash or treasure?

Directly across from Clearview, spread along more than a half-mile of West 103rd Street, Panasonic’s $4 billion electric vehicle battery plant is rising on the grounds of the old ordnance works. Scheduled to open in 2025 with some 4,000 workers, nothing since World War II has so impacted De Soto, a mostly rural town of 6,500. That includes fueling rumors on the fate of Clearview and its 500 or so residents.

On 70 acres, Clearview, even in its dilapidated state, is worth a small fortune.

Designed as Sunflower Village by Kansas City landscape architects Hare & Hare, the district in 2014 was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, not for its buildings, but for its layout as an example of the pastoral Garden City Movement. Johnson County this year appraised the property at $6.1 million.

But ever since the Panasonic plant construction began, rumors have swirled among Clearview’s residents, who have been bearing witness to the village’s gradual neglect. Their assumption has been that David Rhodes, whose Olathe company, Wheatland Investment Group, owns six senior living developments in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas, will either put the land up for sale or redevelop it himself. But Rhodes, who has owned Clearview since 2001, claims the topic is rife with misunderstanding.

“I don’t know why that guy’s not repairing more of the empty buildings,” Reidhart said. “I was going to sink more of my own money into the apartment, decorating. Then the rumors started he’s going to sell out. And we’ll be gone.”

Twin brothers Tyler and Ron Buerman, 28, both live in Clearview. Tyler’s been there for five years; Ron for three. They see a similar future.

“It’s a gold mine,” Ron Buerman said. “Basically, what I think they’re going to do is either this will be a damn parking lot for Panasonic, or apartments.” He looked at the houses all around him.

“I mean that one’s vacant. That one’s got a hole in it. That’s one vacant,” he said. “People now, they’re like, ‘Oh, well, this is the end of it.’ They’re trying to stay here and kind of squat here as long as possible. People are like, ‘Look, if we’re not going to be here any longer, why am I going to pay rent?’”

In De Soto, there’s no lack of residents who say that unless Clearview gets a major renovation, few would lament its disappearance. That includes Kathy Ross, the president of the De Soto Kansas Historical Society.

“If you ask my opinion, somebody should buy it, do away with the historic site crap, and just bulldoze all of it,” Ross said.

Age 86, lifelong De Soto resident Buddy Kobler called the place “trash.” “They ought to tear it all down and do something with it. I don’t know what,” he said.

“It’s just kind of a rental place that’s falling apart,” Loya Coker Beery said. Age 80, she is a descendant of the Coker family that has owned businesses in and around De Soto for 120 years. “A lot of the houses have already completely fallen apart.”

‘A town in itself!’

The irony, they suggested, is that it is partly Clearview’s rich historic past, when it was erected as Sunflower Village, that makes them think the development may have degraded beyond being saved.

“There used to be a grocery store there,” Ross said. “It had its own post office. There used to be a bowling alley. There was a theater.”

Local lore — unconfirmed — has it that in 1956, a young University of Kansas basketball player, Wilt Chamberlain, may have briefly set pins at the bowling alley as a part-time job until the athletic department asked him to quit out of worry that an errant ball might clip one of the star’s ankles.

What is certain is that , beginning in August 1943 when its first residents moved in, Sunflower Village was its own vibrant community, unincorporated in Johnson County, and still more than 50 years away from being annexed by De Soto.

Built by the federal government, operated by the Federal Public Housing Administration, is was in effect a company town for some of the of thousands of workers hired by The Hercules Power Co.

The initial build: 175 concrete block buildings containing 852 apartments. On Aug. 1, 1943, The Star covered the arrival of the first tenants in story headlined, “It’s moving day.”

Photos showed the spartan rooms. Because of wartime restrictions on metal and wood, cabinets were open shelves. Closets had no doors. Ice boxes had no metal. Faucets were plastic. Floors were concrete.

“Rental rates, ranging from $29 to $36.50, include all principal utilities,” the story said.

Acres were set aside for victory gardens. There were two ponds.

“SUNFLOWER is a TOWN in Itself!” a 1944 ad exclaimed to workers, with an inset photo of a new Walgreens. “The dwellings include two, three, four and five room apartments which are equipped with private bath, water heater, and kitchen work table. Garbage and trash pickup, daily mail and ice delivery, and light globes are furnished without additional charge. Schooling for both grade and high school students is available without tuition.”

Within a year, 459 families — some 1,650 residents — called Sunflower home. Eventually, the community would have its own bar, restaurant, grocery store, dry cleaner, Sears catalog store, shoeshine parlor, beauty shop and barber. To meet demand, the government hauled in 680 more prefabricated buildings, this time made of wood, brought in from Niagara Falls. Wearing poorly, they were gone within a decade.

Post-War War II, Sunflower housed returning veterans and KU students. During the Korean War, production at the plant burgeoned. After the war’s end in 1953, employment fell. Residents left. By the time, in 1960, that Sunflower was turned over to its first private owner, all but nine buildings were boarded up. According to a narrative submitted for Sunflower’s historic status, the village was a wreck.

Oklahoma developer Louis H. Ensley vowed to remake Sunflower into “a choice place to live.”

“Low rent,” he told local media, “is the secret.”

The population grew to 1,800. But the low rent paralleled slowly increasing crime and a poor reputation. In 1971, Ensley sold Sunflower to Kansas City developer Paul Hansen, who put in a pool, eventually leasing mostly to retirees. He gave it a new name, promoting a better future for “the village” at “Clearview City.”

“The citizens of Johnson County can now look at Clearview City and be proud,” he told The Daily News in Olathe in 1974. “That wasn’t true two years ago.”

But seven years later, on July 1, 1981, Hansen was killed with 113 others in the tragic Hyatt Regency Hotel skywalk collapse in Kansas City. In 1988, Jim Bush took ownership of Clearview, returning it to general rentals. Sunflower persisted ,through the ordnance plant’s eventual shutdown in 1992, through years of toxic waste cleanup and through years of unrealized plans to turn the ordnance site into, among proposals, an Oz theme park or the home of the Kansas Speedway.

In 1998, De Soto annexed Clearview, making it part of the city. In 2001, Rhodes bought the complex.

‘Major rehab’

Despite what tenants might presume, Rhodes said in a recent interview with The Star that his plan is not to tear the place down. It’s to fix it up.

“We put this on the National Register of Historic Places,” he said. “And the purpose is to preserve it, and rehab it. Our desire — if we can get the assistance of the state of Kansas and the city of De Soto — will be to do a major rehab.”

Rhodes said he is aware that Clearview looks neglected. About 100 of around 340 apartments stand empty or are boarded up. That has been “intentional,” he said, as the plan is “not to throw good money after bad.” The idea, instead, is to keep some apartments occupied while emptying others to be rehabbed. Tenants would then gradually vacate the old apartments to move into the new.

“The desire is not to have any more warehouses,” he said of the industrial buildings he sees going up in the area to support the Panasonic plant, “but to provide some workforce affordable housing. We felt like it was a good opportunity to bring on additional housing for potential workers, people who need housing. And, yes, the outside is in disrepair. But that’s been done because we want to do a major rehab inside and out.”

Rhodes declined to discuss financing for the project, which would include everything from buildings to sidewalks to sewer lines.

“I don’t know that I really want to comment on how we’re going to do that financial-wise,” he said, “but we will do it so it remains affordable.”

The Star, however, through a Kansas Opens Records Act request to the city of De Soto, received a copy of an application for city economic incentives completed by Rhodes in January 2023 that, at that time, set the price of the project at $55 million.

The application said that Rhodes, through Clearview Village Inc., was seeking to rehab 340 apartments, starting later that year.

“In addition to grants and other funding sources,” the application read, “the Owner intends to apply for federal and state low-income housing tax credits and historic rehabilitation tax credits in order to subsidize the costs of developing the project.”

Kristen Johnson, the historic tax supervisor for the Kansas State Historical Society, confirmed to The Star that the agency has been in discussions regarding the Sunflower Village Historic District.

“I have been working recently with Mr. Rhodes on a State Tax Credit Project for the roof repair on several of the buildings within Sunflower Village,” Johnson emailed. “I have also spoken with Mr. Rhodes and a preservation consultant … regarding a larger rehab of the complex. Most of that discussion has been logistics of how to structure a project for such a big area.

“But I can say that there have been discussions of a large scale rehabilitation taking place. The roof repairs I approved recently were more of an emergency.”

De Soto city leaders want to see Clearview improved.

“We know the owner has been pursuing grants or state incentives for a rehabilitation project, and we’ve been supportive of those efforts,” Mike Brungardt, De Soto city administrator, told The Star in an email. “We’ve seen some preliminary concepts … but there has been no formal planning or building permitting applications filed to date.”

Rhodes said he is ”hopeful” to start in 2025.

“We’ve attempted to be a conscientious landlord,” he said. “It does not have curb appeal. But when you get inside — for the amount of square footage you have, and the price you pay for rent — it is very affordable. And we would like to continue that.

“The desire is to make the outside as good as the inside.”

Cozy, quiet … cracks

The insides are as different, sometimes as surprising, as the tenants.

For Adelaida Romero-Carlos, 41, her husband and daughters Matilda, 13, and Abigail, 8, Clearview has been a cozy world for 15 years. The kids share a one room and a bunk bed. The De Soto school bus picks them up and drops them off. Their friends are here.

“I like it,” Romero-Carlos said in a light Spanish accent, “because everybody knows the people. It is secure. I like because no stores, no other peoples coming here, just the families.”

For another renter, the concrete block home isn’t a home at all. It’s been gutted and turned into a working garage for his muscle and classic cars.

“It is a good place,” Omar Bonilla, 42, said of his two-bedroom, two-bath, shared with his wife and three children. Rent: $1,020. “Or it was,” he continued, up until the time Panasonic began its construction, igniting blasts that sent cracks across their floor and walls.

“When they did that, the whole house began to shake,” he said, pointing to cracks beneath the vinyl floor covering, separations in the bathroom and at the baseboards.

“We are getting a lot of bugs inside the house,” Marbella, his wife, said.

Like others, they see the empty buildings, and boarded windows, and, lacking any certain explanations, continue to wonder about Clearview’s future and their own.

“One time a friend came in and she said, ‘Marbella, have you been looking for an apartment or a house?’ I’m like, ‘No. Why?’ ‘Oh, because I hear they’re going to tear up the whole place.’ I said, ‘Really?! We haven’t had any notice about it.’”

“I’m pretty sure if that happens,” Omar said, “they’re going to kick us out. What are we going to do?”

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  XRP

XRP  USDC

USDC  Solana

Solana  TRON

TRON  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether